These are the woes of slaves;

They glare from the abyss;

They cry, from unknown graves,

“We are the witnesses!”

– Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, The Witnesses

Just a 50 minute drive from Portland, OR, you enter an entirely different world – old growth forest covering the mountains, steep cliffs, the majestic Columbia slowly making its way through a gorge that was carved millennia ago into the landscape. If you happen to visit the Gorge Museum in Stevenson, WA on your way East, you can currently immerse yourself in yet a different world still – a collection of quilts that witness the life, skills and wisdom of a 19th century slave, handed down to next generations. Named the Hartsfield Collection after the family who preserved the legacy of one of their ancestors, a former slave, it serves as an entry into the patterns of both slave life and quilting.

Crossroads Quilt, Late 19th Century

The accumulated heirlooms are part of a collection created and persevered by a family dedicated to witnessing history, including that of their very own ancestor(s.) The current generation is represented by Jim Tharpe, who realized that the quilts, made by five different seamstresses across four generation from 1850 – 1960, were of enormous significance and able to tell a story that resonated beyond what we know theoretically about quilting during slavery. His insights and persistence to bring something of significant historical value to our eyes made it possible that these quilts are now making their rounds in museums keen, among others, on teaching history.

The exhibition is expertly guided by signage that tells you about the provenance and meaning of each quilt (as displayed in my photographs.) You can learn even more detail in a book written by Tharpe and available at the museum, that explains the family history, the creation of the collection and his purpose in investing his passion, time and energy into the preservation of the collection.

The earliest quilt, the Slave Quilt (1850), was made as personal bedding by a thirteen-year old slave, Ms. Molly, who was sold away from her family to a plantation in Whitlock, Tennessee. Close inspection reveals not just use and tear, but also bloodstains. We will never know if from the whip, rape or childbirth – she bore two sons to her Master, who were fortunately not sold away from the household. Faded, easily overlooked, they nonetheless instill a sense of the horrors of the life that then-child must have experienced.

She taught her skills to her own children and in-laws after the Civil War was won. Eventually the family relocated North, but still trecked to Tennessee many years later to visit relatives that remained there, often under the shadow of racism that put travelers in danger.

Danger while traveling was, of course, one of the hallmarks of the Underground Railroad movement, helping slaves to escape their masters and start a new life somewhere supposedly more safe, if not free. One of the ways to prepare, or to warn, or to help people finding their ways and supportive allies, was a language of communication contained in quilts. Specific patterns indicated specific requirements or signals to those on the move.

Expert quilters might be well aware of this history, lots written about it. For the rest of us, even though we are aware of forms of communication not contained in written words – just think of the knotted messages of the Incas, Semaphore or Braille, sign-language or Morse code – we might not know about the meaning of patterns around in quilts. I certainly had no clue, even though I count two expert quilters among my friends.

The exhibition then, really opened my eyes not just to the creativity of individual seamstresses and the beauty of their resulting work, but the meaning behind much of what was in front of me, guiding me into a world that lacked all the privilege of my own and that holds historical lessons we should well heed.

In general, there were ten quilt codes to be used for the journey, with just one displayed at the time. A sampler with all the codes in small form, secretly passed around, served as a teaching device for memorization of the patterns. The quilts were displayed in windows or hung out with the washing to inform the travelers. The backs and fronts were joined by twine tied two inches apart, with patterns of knots mapping the existence and distance of safe houses along the route. (Ref.)

Here are some of the patterns used in the quilts on exhibit (note, there are variations in names across states, not captured here):

The variety of the artistry shown is helpful for us to understand how form, function and aesthetics go hand in hand. The dedication of this family to relating the skills to subsequent generations and preserving, despite many moves across the U.S. what is a treasure, makes it very clear that they know about the importance of history, and the ways its official telling needs to be supplemented by people who’ve actually experienced it from diverse perspectives.

I was particularly moved to see the oldest and most recent of the quilts exhibited in juxtaposition. The latter was a graduation present to Jim Tharpe, with an inconspicuous love letter stitched into the sidebars, just as the blood stains were inconspicuous on the former. It brought home to me that it is not enough to be exposed to something in order to witness. You have to look. Look carefully. Not leave it to those lying at the bottom of the ocean.

The effort to bury parts of our history, efforts yet again sweeping our country in the form of curriculum changes, prohibition of certain books, elimination of programs dedicated to Black History studies and the like, is hopefully counter-acted by exhibitions like the current one. It brings history alive in front of your very eyes and encourages conversations with those you bring to this show, children included, about what is contained in these beautiful quilts and why it had to be kept secret.

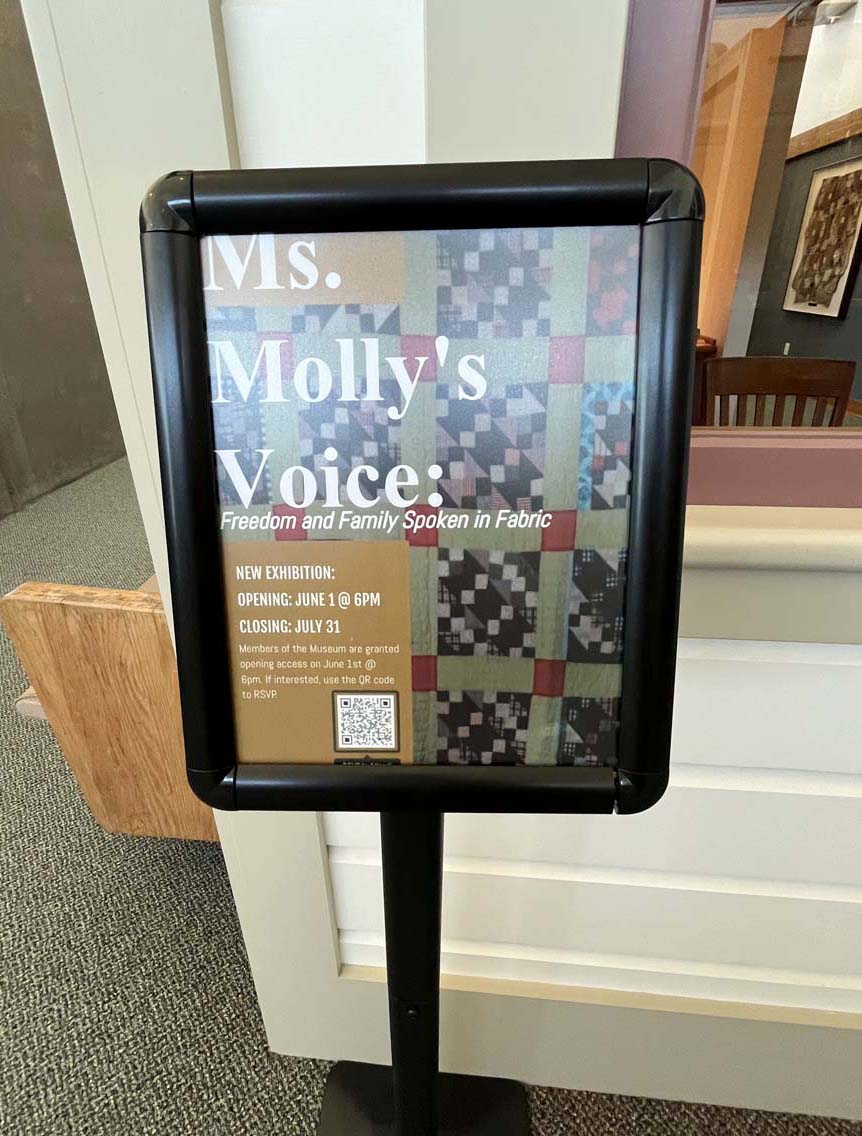

Columbia Gorge Museum

Ms Molly’s Voice: Freedom and Family Spoken In Fabric

June 1 – July 31st, 2024

Open Everyday: 10:00am – 5:00pm

990 SW Rock Creek Dr, Stevenson, WA 98648

Special Event:

“In celebration of Juneteenth, the Columbia Gorge Museum will be hosting an open event where attendants will focus on creating quilt patterns in a dialogue with the patterns and skill of Ms. Molly. Take a guided experience through the quilt exhibition and thanks to some amazing Columbia Gorge quilters, create your own family document in a quilt square.

This event takes place June19th between 2 p.m. and 4 p.m. All are welcome!

If you would like to attend this event, simply RSVP here!“

Here is the full poem from which I took the quotation at the beginning of the review.

The Witnesses

In Ocean’s wide domains,

Half buried in the sands,

Lie skeletons in chains,

With shackled feet and hands.

Beyond the fall of dews,

Deeper than plummet lies,

Float ships, with all their crews,

No more to sink nor rise.

There the black Slave-ship swims,

Freighted with human forms,

Whose fettered, fleshless limbs

Are not the sport of storms.

These are the bones of Slaves;

They gleam from the abyss;

They cry, from yawning waves,

“We are the Witnesses!”

Within Earth’s wide domains

Are markets for men’s lives;

Their necks are galled with chains,

Their wrists are cramped with gyves.

Dead bodies, that the kite

In deserts makes its prey;

Murders, that with affright

Scare school-boys from their play!

All evil thoughts and deeds;

Anger, and lust, and pride;

The foulest, rankest weeds,

That choke Life’s groaning tide!

These are the woes of Slaves;

They glare from the abyss;

They cry, from unknown graves,

“We are the Witnesses!”